|

US Navy "Project X-Ray"

Couffer's (1992) enjoyable book, "Bat Bomb,"

is a great story about an idea that wasn't.

The following quote from McCracken's correspondence with R.A. von Doenhoff of the United States National

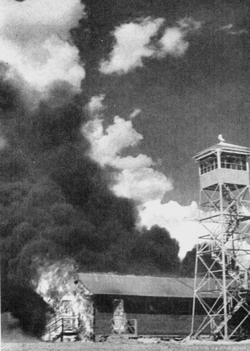

Archive concerning Project X-Ray (McCracken, 1990) briefly summarizes this debacle. "Project X-Ray was an experiment undertaken by the Department of the Navy to determine if incendiary devices attached to bats would be useful if they were released form aircraft over major Japanese cities. The theory was that the bats would be released just before dawn with incendiary devices with timers attached to each bat. As daylight approached, the bats would head for dark recesses of wooden Japanese houses. When the bats were safely asleep, the incendiary devices would ignite, thus producing a conflagration of unprecedented proportions. A test run of this theory was carried out in the southwestern United States. However, the advent of the atomic bomb rendered this experiment moot." The Bat Bombers October 1990, Vol. 73, No. 10 After the bats set fire to a hangar and a general's car, the Army Air Forces had seen enough of the experiment. DR. Lytle S. Adams, a dental surgeon from Irwin, Pa., was vacationing in the southwestern US on December 7, 1941. Like millions of Americans, he was shocked at the news from Pearl Harbor and couldn't believe Japan had been able to mount such an attack. In those days, "Made in Japan" meant cheap, shabby, and inferior. Americans' image of Japan was of crowded cities filled with paper-and-wood houses and factories. Dr. Adams pondered how the US could fight back. In a 1948 interview with the Bulletin of the National Speleological Society, Dr. Adams recalled: "I had just been to Carlsbad Caverns, N. M., and had been tremendously impressed by the bat flight. . . . Couldn't those millions of bats be fitted with incendiary bombs and dropped from planes? What could be more devastating than such a firebomb attack?"  Dr. Adams went back to Carlsbad and captured some bats. At home, he read everything he could find about the tiny flyers. He learned that there are nearly 1,000 species around the world and that each bat lives up to thirty years. The most common bat in North America is the free-tailed, or guano, bat, a small brown mammal that may catch more than 1,000 mosquitoes or gnat-sized insects--a load twelve times its own size--in a single night. Weighing about nine grams, it can carry an external load nearly three times its own weight.

Dr. Adams went back to Carlsbad and captured some bats. At home, he read everything he could find about the tiny flyers. He learned that there are nearly 1,000 species around the world and that each bat lives up to thirty years. The most common bat in North America is the free-tailed, or guano, bat, a small brown mammal that may catch more than 1,000 mosquitoes or gnat-sized insects--a load twelve times its own size--in a single night. Weighing about nine grams, it can carry an external load nearly three times its own weight.On January 12, 1942, Dr. Adams sent to the White House a proposal to investigate the possible use of bats as bombers. In those days, well-meaning citizens were proposing all kinds of warfare ideas, most of them impractical. However, this idea, after being sifted through a top-level scientific review, became one of the very few given the green light. It was passed to the Army Chemical Warfare Service (CWS) for further inquiry in conjunction with Army Air Forces. The official CWS history states simply: "President Roosevelt OK'd it and the project was on." Dr. Adams and a team of field naturalists from the Hancock Foundation, University of California, immediately set to work and visited a number of likely sites where bats would be available in large quantities. Bats are found mostly in caves, though great numbers roost in attics, barns, and houses, under bridges, and in piles of rubbish. "We visited a thousand caves and three thousand mines," Dr. Adams later related. "Speed was so imperative that we generally drove all day and night when we weren't exploring caves. We slept in the cars, taking turns at driving. One car in our search team covered 350,000 miles."

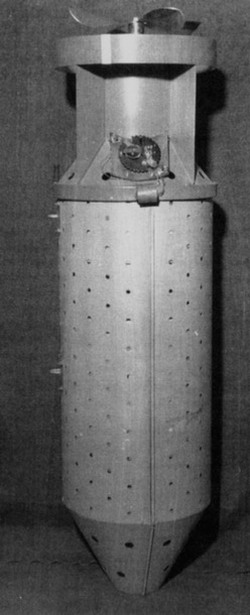

The largest bat found was the mastiff, which has a twenty-inch wingspan and could carry a one-pound stick of dynamite. However, the team found there weren't sufficient numbers available. The more common mule-eared, or pallid, bat could carry three ounces, but naturalists determined it wasn't hardy enough for the project. Finally, the team selected the free-tailed bat. Though it weighed but one third of an ounce, it could fly fairly well with a one-ounce bomb. The largest colony of freetailed bats found by Dr. Adams' naturalists, some twenty to thirty million, was in Ney Cave near Bandera, Tex. The colony was so large, according to a report by CWS Capt. Wiley W. Carr, that "five hours' time is required for these animals to leave the cave while flying out in a dense stream fifteen feet in diameter and so closely packed they can barely fly." Collection of the bats was not difficult. Three nets, about three feet in diameter, on ten-foot poles were passed back and forth across the cave entrance as the bats flew out. As many as 100 could be caught on three passes. They were removed from the nets and placed in cages in a refrigeration truck. Dr. Adams took some to Washington, releasing them in the War Department building to show Army officials how they could each carry a dummy bomb. In March 1943, authority to proceed with the experiment came from Hq. USAAF. Subject: "Test of Method to Scatter Incendiaries." Purpose: "Determine the feasibility of using bats to carry small incendiary bombs into enemy targets." The bats' habits were studied intently. Meanwhile, Dr. L. F. Fisser, a special investigator for the National Defense Research Committee, began to design bombs light enough to be carried by bats. He did not find it difficult, because there was a precedent for miniature incendiaries. England's principal firebombs, used in World War I, were called "baby incendiaries." Filled with a special thermite mixture, these bombs weighed 6.4 ounces each. Arming the Bats Dr. Fisser designed two sizes of incendiary bombs for the bomber-bat experiments. One weighed seventeen grams and would bum four minutes with a ten-inch flame. The other weighed twenty-eight grams and would burn six minutes with a twelve-inch flame. They were oblong, nitrocellulose cases filled with thickened kerosene. A small time-delay igniter was cemented to the case along one side. The time-delay igniter consisted of a firing pin held in tension against a spring by a thin steel wire. When the bombs were ready to use, a copper chloride solution was injected into the cavity through which the steel wire passed. The copper chloride would corrode the wire; when the wire was completely corroded, the firing pin snapped forward, striking the igniter head and lighting the kerosene. Small time-delay smokebombs were also designed so test flights of bats could be traced by ground observers. They burned for thirty minutes with a yellowish flame that could be seen several hundred yards away at night; white smoke was also emitted. To load a bomb aboard a bat, technicians attached the case to the loose skin on the bat's chest by a surgical clip and a piece of string. Groups of 180 were released from a cardboard container that opened automatically in midair at about 1,000 feet, after which, says the CWS history, "bats were supposed to fly into hiding in dwelling and other structures, gnaw through the string, and leave the bombs behind." In May 1943, about 3,500 bats were collected at Carlsbad Caverns, flown to Muroc Lake, Calif., and placed in refrigerators to force them to hibernate. On May 21, 1943, five drops with bats outfitted with dummy bombs were made from a B-25 flying at 5,000 feet. The tests were not successful; most of the bats, not fully recovered from hibernation, did not fly and died on impact. The bat-bomber research team was transferred a few days later to an Army Air Forces auxiliary airfield at Carlsbad, N. M.

Complications Arise There were many complications. Many bats didn't wake up in time for the drops. The cardboard cartons did not function properly, and the surgical clips proved difficult to attach to the bats without tearing the delicate skin. When these problems were somewhat resolved, new bats were taken up for drop tests with dummy bombs attached. Many simply took advantage of their freedom to escape or refused to cooperate and plummeted to earth. The Army tests were called off on May 29, 1943, and Captain Carr prepared a final report. "The bats used at Carlsbad weighed an average of nine grams," he wrote. They could carry eleven grams without any trouble and eighteen grams satisfactorily, but twenty-two grams appeared to be excessive. The ones released with twenty-two-gram dummies didn't fly very far, and three returned in a few minutes to the building where we were working. One flew underneath, one landed on the roof, and one attached itself to the wall. The ones with eleven- gram dummies flew out of sight. The next day an examination of the grounds around a ranch house about two miles away from the point of release disclosed two dummies inside the porch, one beside the house, and one inside the barn." More than 6,000 bats were used in the Army experiments. In his secret report, dated June 8, 1943, Captain Carr concluded that a better time-delay parachute type container, new clips, and a simplified time-delay igniter should be designed if further tests were to be carried out. He also recommended a six-week controlled study of bats during artificial hibernation. After this, he said, another test should be conducted with 5,000 bats. Captain Carr reported tersely that "testing was concluded . . . when a fire destroyed a large portion of the test material." He did not mention that, in one test, a village simulating Japanese structures burned to the ground. Nor did he state that a careless handler had left a door open and some bats escaped with live incendiaries aboard and set fire to a hangar and a general's car. Records do not reflect the general's reaction, but he could not have been pleased. Shortly thereafter, in August 1943, the Army passed the project to the Navy, which renamed it Project X-Ray. The Sea Services Take Over In October 1943, the Navy leased four caves in Texas and assigned Marines to guard them. Dr. Adams designed screened enclosures that were prefabricated at Hondo Army Air Field and placed over the cave entrances to capture the bats. A million could be collected in one night if necessary. By that time, the Navy had handed the project off to the Marine Corps. The first Marine Corps bomber-bat experiments began on December 13, 1943. In subsequent tests, thirty fires were started. Twenty-two went out, but, according to Robert Sherrod's History of Marine Corps Aviation in World War II, "four of them would have required the services of professional firefighters. A new and more powerful incendiary was ordered." Full-scale bomber-bat tests were planned for August 1944. However, when Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King, Chief of Naval Operations, found that the bats would not be combat-ready until mid-1945, he abruptly canceled the operation. By that time, Project X-Ray had cost an estimated $2 million. Dr. Adams was disappointed. He maintained that fires generated by bomber bats could have been more destructive than the atomic bombs that leveled Hiroshima and Nagasaki and ended the war. He found that bats scattered up to twenty miles from the point where they were released. "Think of thousands of fires breaking out simultaneously over a circle of forty miles in diameter for every bomb dropped," he said. "Japan could have been devastated, yet with small loss of life."

By James M Powles, Command, Issue 42, March 1997 When Dr Lytle Adams, a dental surgeon from Pennsylvania, first heard the news of the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbour, he wracked his brain to come up with what he believed an appropriate reply to so dastardly event. On a recent visit to New Mexico's Carlsbad Caverns he'd seen tens of thousands of bats. It occurred to him the flying mammals could be equipped with small, delayed-action incendiary devices, then released over the cities of japan during daylight. Since bats seek shelter from sunlight, they would instinctively dive inside buildings in search of darkness. When the incendiary bombs they carried went off, the mostly wood and paper structures of Japanese cities would quickly catch fire, thus enabling whole urban areas to be reduced to ash in a short time. Adams wrote up his scheme in a letter and sent it off to the White House, where FDR eventually gave it his go ahead. The plan was given top priority and Adams was put in charge of developing it. The first problem involved lay in finding the rigth type of bat in large enough numbers. Adams and a team of naturalists scoured the country until they finally decided on one species popularly called "Mexican Free Tails." Though each typically weighed only half an ounce, they could generally carry up to twice that amount of weight and still fly. The largest colony of Free Tails, some 25 million, existed near Bandera, Texas. Two caves in that area, Ney and Bracken, were selected as collecting sites. Two camps were set up nearby with US Marines to guard their perimeters. Wire screens were put in place across the mouth of each cave, equipped with gates that, when open, still allowed the bats to came and go as they pleased. When closed, of course, the bats inside were trapped and could easily be caught. The next step was designing the bombs. That task was assigned to Dr Louis F Fieser, a chemist from the National Defense Research Committee who'd already devised other small incendiary devices. His new bat bombs contained napalm (then still called "jellied gasoline") held in celluloid shells. They were to be placed on surgical clips attached to the bats' chests by string. (It was compassionately hoped the bats might save themselves from immolation by biting through the strings once under cover, but few did.) The next step was finding the appropriate transportation to the skies over Japan. Such a mission would be aloft long enough to require the bats be fed enroute - a difficult job, since each one daily ate many times its own weight in insects. The problem was so difficult it was finally decided to induce the bats to hibernate during the flight. Numerous attempts to do that were made before the scientists discovered exposing the animals to temperatures below 40 degrees F did the trick. Further, all but a few in each experimental batch always reawakened upon warming. Since the planes that would carry the bats over Japan had to fly at high altitudes to avoid ground fire, it then became necessary to develop some method of releasing them close to the ground. They therefore developed sheet metal containers, resembling conventional aerial bombs, that each held about 1,00 bats. The containers would be dropped at altitude and float down on parachutes. At 1,000 feet an altitude sensor would open the containers, allowing the bats to go free. That release also activated each bat's delayed action bomb fuse. It was determined a B-25 could carry about 25 containers. That bat bomb program wracked up two successful test attacks. The first was actuallly an accident, occurring when a number of bats got loose during testing of the flight containers at Carlsbad Air Force Base in June 1943. Upon escaping, the bats immediately sought the shelter of the airfield buildings, setting several of them ablaze. A hangar, barracks and some other structures were burned to the ground. The second test attack - this one actually planned - occurred in the December of that year under USMC supervision at the Dugway Proving Grounds in Utah. The bats were let loose into a specially built village of Japanese style houses. Again, in a short time the area was engulfed in flame. But despite the successful tests, the project was cancelled early in 1944. By that time the leadership in Washington had come to put their faith in another secret weapon then completing development - the atomic bomb. |